"Women is Losers" - Janis Joplin

On Bullying

53 years later, misogyny continues to tarnish Joplin’s legacy.

While the pages of rock magazines might give you a more straightforward diagnosis — accidental heroin overdose at the age of 27 — and it's true the act was finalized by a needle, Janis Joplin’s demise came under the grips of something more sinister.

Misogyny killed Janis Joplin.

And 53 years later, it continues dancing on her grave.

In September, The New York Times published an incendiary interview with Jann Wenner, co-founder of Rolling Stone and its former editor-in-chief, about his latest book, The Masters, a collection of interviews with seven white male rock stars who Wenner considers the zeitgeist of rock n roll. They include Mick Jagger, Pete Townshend, and Bruce Springstein. When asked why The Masters doesn’t include any women or Black musicians, Wenner summed up his controversial legacy by saying the quiet part of his bigotry out loud:

“Just none of them were as articulate enough on this intellectual level,” Wenner declared. “It's not that they're inarticulate, although, go have a deep conversation with Grace Slick or Janis Joplin. Please be my guest.”

Wenner was chucked from his board seat on the Rock n Roll Hall of Fame in response, though his behavior isn’t new. This is the same institution that inducted over 350 musicians with only 8% of them women. This is the same magazine which in 1971 named Joni Mitchell as “Old Lady of the Year.” Music critic Ellen Willis wrote to Rolling Stone co-founder Ralph Gleason in 1970 that she found the magazine to be “viciously anti-woman…RS habitually refers to women as chicks and treats us as chicks, i.e. interchangeable cute fucking machines.” She also criticized its politics: “When a bunch of snotty upper-middle class white males start telling me that politics isn’t where it’s at, that is simply an attempt to defend their privileges.”

If you were to take Wenner’s condescending advice to try and “have a deep conversation” with Joplin, you’d find that she was profoundly impacted by the culture of misogyny that Wenner helped create. She spoke about it openly. In what would be her final interview, recorded just four days before she died, Howard Smith of the Village Voice begins by reminding Joplin that their original interview had been rescheduled because “some article by Rolling Stone had just come out putting you down.” Smith asks if that is the reason why she avoided an interview with him until now. "That was a pretty heavy time for me," she responded.

"It was really important, you know, whether people were going to accept me or not. I should be able to get past that. Even though I know those are just assholes who don’t know what they're talking about and I should just continue with my music and let them come to the show and listen or go home and beat off. I don't care if they dig it. I should be able to do that but inside it really hurts me.”

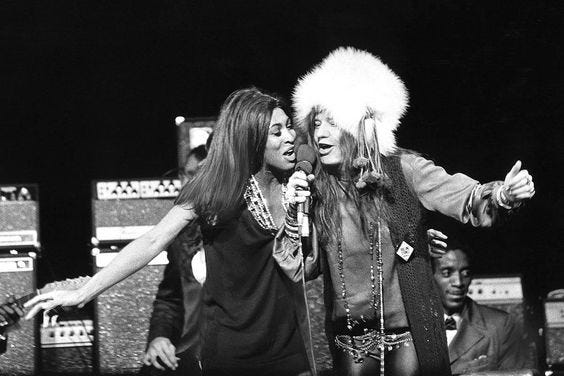

During her painfully short-lived, four-year career, Joplin became a star in a club reserved exclusively for men. The price she paid for admission was rampant sexism. Music critic Robert Christgau wrote of her breakthrough performance at the Monterey Pop Festival, “her left nipple erect under her knit pantsuit looking hard enough to put out your eye.” Male rockers were allowed to exude sex without much mention from journalists. In contrast, women who tried to be sexy were often depicted as classless. Tina Turner was called raunchy. But when Mick Jagger tore off her skirt without permission during a duet, he was lauded as a showman. For Joplin, the double-standard was isolating. “A man can do it (music) as a gig because he knows he can get laid tonight. Women, to be in the music business, give up more than you know. You give up a home, children, friends, any constant in the world except music. That's the only thing you've got left in the world is music.”

These sentiments are echoed in the 1967 song she wrote and released with Big Brother and the Holding Company.

Women is losers, oh,

Say honey women is losers.

Well, I know you must have heard it all,

And everywhere

Men always seem to end up on top.

Joplin had sought fame to protect herself from bullies. Growing up in a conservative Texas town, she was attacked for her weight, her acne scars, her “beatnik” personality. Boys called her “pig” and “freak.” In college at UT Austin, she was voted into an “Ugliest Man on Campus” contest as a fraternity prank. “They laughed me out of class, out of town, out of the state,” she explained on The Dick Cavett Show. In an excerpt from the Little Girl Blue documentary, her younger sister Laura revealed that Joplin had dropped out of college and ran away to San Francisco because “It became increasingly harder to fit into a group of angry men who liked to pick on her.”

Rock n roll did not prove to be an ally — in fact, almost no one did. Though her reputation for fluid sexuality liberated millions of young women from the stranglehold of restrictions placed on them in the ‘60s, she wasn’t accepted as part of the revolution according to certain factions of the Women’s Liberation Movement. During her interview with the Village Voice in 1969, Smith asked about this contradiction.

Smith: “A lot of women have been saying that the whole field of rock music is nothing but a male chauvinist rip off and I say, ‘What about Janis Joplin? She made it,’ and they say, ‘oh her.’ It seems to bother a lot of women’s lib people that you're so upfront sexually.”

Joplin: “Well that’s their problem, not mine. I’m representing everything they say they want. You are what you settle for. If they settle for being somebody’s dishwasher, that’s their own fucking problem. If you don't settle for that and you keep fighting, you’ll end up being anything you want to be. How can they attack me? I’m just doing what I want to and doing what feels right and not settling for bullshit.”

But the truth is, the bullshit got to her. Her image as the free-lovin, carefree spirit masked her pain, which she diluted with copious amounts of drugs, booze, and sex.

Joplin was intimately linked to several of her male peers including Kris Kristofferson, Leonard Cohen, and the founding member of the Grateful Dead, Ron "Pigpen" McKernan. She also had relationships with women, including Jai Whitaker. They were together for two years until Whitaker broke it off because of Joplin's drug use and infidelity. “Janis was a walking contradiction,” Whitaker said. “I think she wanted kids, but I also think she really felt very good with a woman, yet she punished herself for that feeling. She didn’t think it was right.”

When Joplin died, rock n roll’s tragic loss inspired some of its best songs:

“Pearl," by the Mamas and Papas:

"Here's a wish for a runaway girl

Here's a prayer for honkytonk Pearl.”

"In the Quiet Morning," by Joan Baez:

"That poor girl tossed by the tides of misfortune

Barely here to tell her tale

Rolled in on a sea of disaster

Rolled out on a mainline rail.”

“American Pie,” by Don McLean:

"Met a girl who sang the blues

And I asked her for some happy news

But she just smiled and turned away.”

Perhaps the song that best captures Joplin’s demons is Leonard Cohen's "Chelsea Hotel No. 2:"

"You fixed yourself, you said,

'Well never mind

We are ugly but we have the music.”

Now, 53 years after her death, rock n roll’s most smug cryptkeeper, Jann Wenner, continues to negate Joplin’s legacy. Along with all other women and every single Black musician, Joplin wasn’t considered “deep” enough to be a true philosopher of his revisionist rock history. The thing is, Wenner’s views don’t just reveal the bias of one person, existing in a vacuum. They shake echoes through the foundation of popular music for the last 60 years. And the erasure has to stop.

Here’s hoping that today we will not only stand up to the bullies, not only persist, not only take on the weight of our own resilience, but actually stop them. We can actually re-claim our legacy in rock history as women, queer and trans people, and people of color.

Did you catch our last issue?

No.19 - "Rough Boys" - Pete Townshend

When aggression became an albatross, Pete Townshend found his feminine side.

Loved this read. I've always loved Janis and felt weirdly protective of her though I couldn't say why until I read Holly George Warren's bio. She was so misunderstood and deeply underestimated. Not ironic at all that it was women who could always see what she was trying to do/be and it's women who continue to reclaim and reconstruct her legacy. Thanks!

She shines in Monterey Pop. And a brilliant piece of editing in that film is the cut to Mama Cass in the audience, tears in her eyes, enraptured by Janis’s performance.