Welcome to Songs That Saved Your Life - a weekly newsletter on rock n roll history written from a queer lens. You can access our full archives here. Don’t forget to check out Songs That Saved Your Life Radio!

History can’t erase the legacy of the transgender soul singer who scored a major hit in 1963.

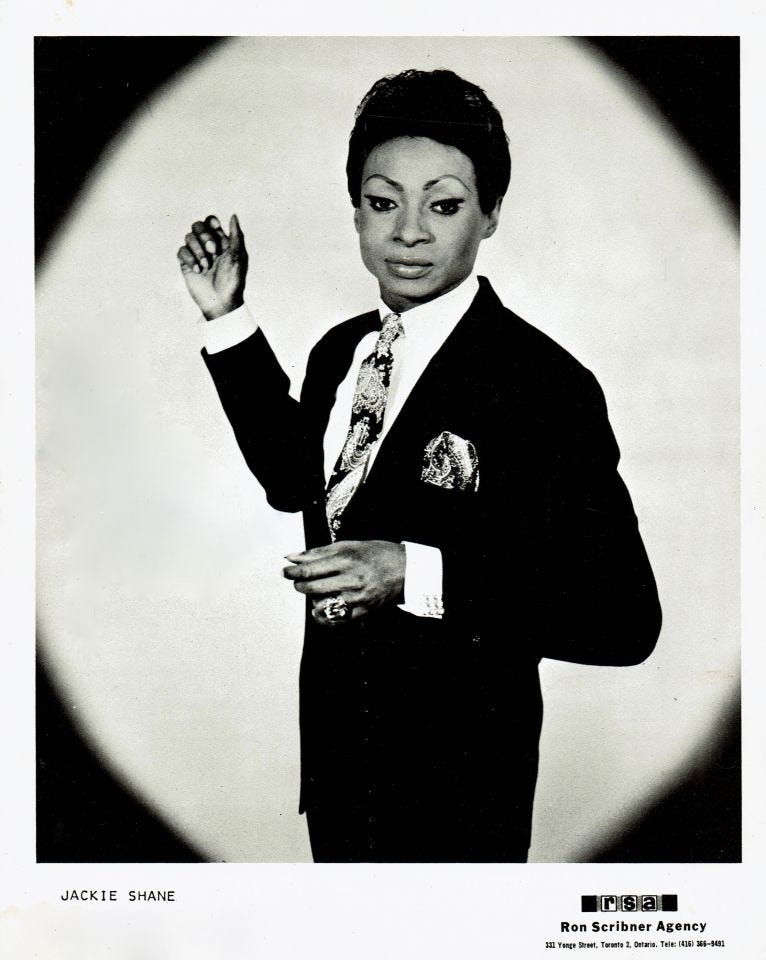

If you haven’t heard of Jackie Shane, the fearless transgender singer who rose to the top of the soul charts in the ‘60s, you will soon. Her story is almost mystical because it refuses to be forgotten. Shane has been consigned to oblivion and rediscovered so many times that it seems the work of divine will. Forces beyond her control place her life into the spotlight as if to rewrite history books for so many trans and queer youth desperate to see themselves reflected.

“I had been discovered,” Shane told the Associated Press in a 2017 phone interview. “It wasn’t what I wanted, but I felt good about it. After such a long time, people still cared. And now those people who are just discovering me, it’s just overwhelming.”

Shane’s story as a transgender youth growing up in the 1950s American South, when rigid laws made life challenging enough to be a Black person, let alone a Black trans woman, was shockingly uneventful. She began wearing her mother’s clothing at the age of 5 and began identifying as a girl aged 13. “They wondered how I could keep the high heels on with my feet so much smaller than the shoe. I would press forward and would, just like Mae West, throw myself from side to side. What I am simply saying is I could be no one else,” she said, adding that she never faced any issues due to her gender identity. Blessed by a supportive mother, Shane began wearing makeup and jewelry outside of the home. “Even in school, I never had any problems,” Shane said. “People accepted me.”

One of the first songs Shane sang as a teenager was Little Richard’s “Lucille,” winning a talent show for her rendition. Shane would eventually study under Little Richard and his band the Upsetters. Because of performers like Richard, gender ambiguity wasn’t a new concept in the R&B circuit. Richard had started his performing career in a traveling tent show as a drag queen named Princess LaVonne. As Preston Lauterbach recounts in his 2011 book The Chitlin' Circuit and the Road to Rock 'n' Roll, which draws heavily on mid-20th century accounts from regional African-American newspapers, it was commonplace for "female impersonators" as they were billed, as well as comedians and magicians to perform as opening acts before a big name musician. The vaudeville concept of a variety show provided a safe cover for queer, nonbinary, and trans performers.

Shane began performing locally in Nashville as a drummer and vocalist. Her talent led to session work for large R&B acts like Big Maybelle and Joe Tex. She also traveled the Chitlin' Circuit with the Cetlin & Wilson carnival, dancing and singing with the tent-show band, along with strippers, ventriloquists and animal acts. But as a Black person living under Jim Crow laws, it was racism that ultimately drove Shane away from Nashville. “You cannot choose where you are born, but you can choose where you call home,” Shane told the AP. “And Toronto is my home.”

She landed a steady gig touring with Frank Motley who was famous for playing two trumpets at once. Shane’s talent as a singer quickly brought her to center stage. “Jackie was a revelation,” said Rob Bowman, who interviewed her at length for the liner notes to the Any Other Way box-set. “Quite quickly the black audience in Toronto embraced her. Within a couple of years, Jackie’s audiences were 50-50 white and black.” According to Bowman, most audiences perceived Shane as a gay man. Her stage outfits were often very feminine pantsuits. In 1963, Shane released her first single, a cover of William Bell’s “Any Other Way.” In the chorus, Shane sings: “Tell her that I’m happy, tell her that I’m gay, tell her I wouldn’t have it any other way.” At the time, the term “gay” was used in popular vernacular to mean “happy.” But here, Shane subverts the original meaning making “Any Other Way” an anthem for queer liberation.

Here you come again,

And you say that you're my friend,

But I know why you’re here;

She wants to know how I feel,

Tell her that I'm happy,

Tell her that I'm gay,

Tell her I wouldn't have it,

Any other way.

The B-side to “Any Other Way” is a further nod to the struggles of the queer community. “Sticks and Stones” is about the hardships that come with being in a queer relationship.

People talkin' tryin' to break us up

Why can't they let us be

Sticks and stones may break my bones

But now talk don't bother me

Shane’s version of “Any Other Way” shot to the No. 2 spot on the Canadian chart, solidifying her as a star. In 1964, she appeared on Night Train, a regional show in Nashville. Her performance was followed by an invitation to perform on The Ed Sullivan Show. The exposure would’ve guaranteed superstardom, but Shane declined the offer when told she’d have to present as male. “His scout came and said: ‘You’re going to have to do this without makeup,’” she explained. “I said: ‘Please stuff it.’ Ed Sullivan looks like something Dr. Frankenstein had a hand in. He’s going to tell me what to do?”

Shane also declined offers to sign with Motown because she refused to stay closeted.

After over a decade of touring, Jackie Shane seemingly disappeared in 1971. With no way to contact her, friends and bandmates worried she’d been murdered. Her legacy lived on among fans and record collectors — but, after decades out of the spotlight, people began to forget about Shane’s music. More than 40 years after her disappearance, Canadian broadcaster Elaine Banks cobbled together a 2010 documentary about Shane’s life and career called I Got Mine: The Story of Jackie Shane. Banks interviewed former bandmates but the documentary ended on an uncertain note, as no one knew where Shane ended up or if she was even still alive.

The story of her disappearance was finally uncovered and instead of the tragedy that many had assumed, the truth was less the nightmare they imagined. Shane’s mother had gotten sick, so she had moved to Los Angeles to care for her, then retired in Nashville. Shane had grown weary from touring and from having to fight for her identity. When she learned of the documentary, she was initially annoyed. But as fans embraced her story, she began to warm up to her new reality. In 2014, Douglas Mcgowan, an A&R scout for archival record label Numero Group, finally reached her via phone in Nashville. After much effort, Mcgowan got her to agree to work with them on a box-set of her live and studio recordings. The album, called Any Other Way, was released in 2017 and nominated for best historical album at the Grammys. News outlets began calling and her photos started appearing in newspapers and magazines after the release of the album. Queer celebrities including RuPaul and Laverne Cox tweeted stories about her.

Shane, who was then 78, had lived a very private life and was not interested in making public appearances. She agreed to interviews only by phone. “It’s like my grandmamma would say, ‘Good things come to those who wait,’” Shane told the AP. “All of the sudden it’s like people are saying, ‘Thank you, Jackie, for being out there and speaking when no one else did.’ No matter whether I initiated it or not, and I did not, this was the way that fate wanted it to be.”

She admitted that she was able to live the life she did because of her absolute refusal to stop loving herself and others.

"When you're different people are not sure how to approach you, so what I've done is, I've loved them first. I had to."

Shane’s reluctant reemergence into the public eye in 2017 was a gift to queer fans whose history is systematically erased. And it’s fortunate that Shane was found when she was because only a year later, she would die in her sleep at her home in Nashville.

"Leave other people alone in the way that they live their lives that you don’t understand. If you want to really know about those people, come to them in friendship! Sit down and let them tell you what their lives are like. But don’t just jump up and holler, “She’s wearing this,” and, “He’s wearing that.” Sit down with a transgender person and let them tell you what their life is like. Sit down with a gay person and let them tell you what life is like for them. Sit with a lesbian and let her tell you about the nature of her life, and what she goes through. How can you judge when you don’t know what it’s about?"

Today, Shane’s face is 22 stories high on a downtown Toronto mural alongside icons like Muddy Waters and B.B. King. A documentary about her life and career will premiere next month at South By Southwest.

Did you catch our last issue?

No.34 - "Fast Car" - Tracy Chapman

”Fast Car” and its buzzworthy Grammy moment have a lot to teach us about healing.

I am sad that I didn't know about her sooner, but I am really glad to know about her now. I already had two of her songs saved on Spotify, so at least I had already enjoyed her music even though I didn't know who she was. They are on a compilation of soul singers called The Sue Records Story.

Thanks for the introduction to Jackie Shane!